Meet Eva Chin, the chef behind Toronto's hottest (and smallest) dining experience

How the ex-Kojin and Avling chef uses food to tell stories about her life, influences, and heritage.

For chef Eva Chin, cooking is all about storytelling.

“Food is story,” says the chef, who’s worked at Kojin and Avling, and who runs the pop-up dining series The Soy Luck Club. So when Chin had the opportunity to open up a dining room in the 26-seat back room of Hong Shing on Dundas, she knew that playing with food and story would be the goal.

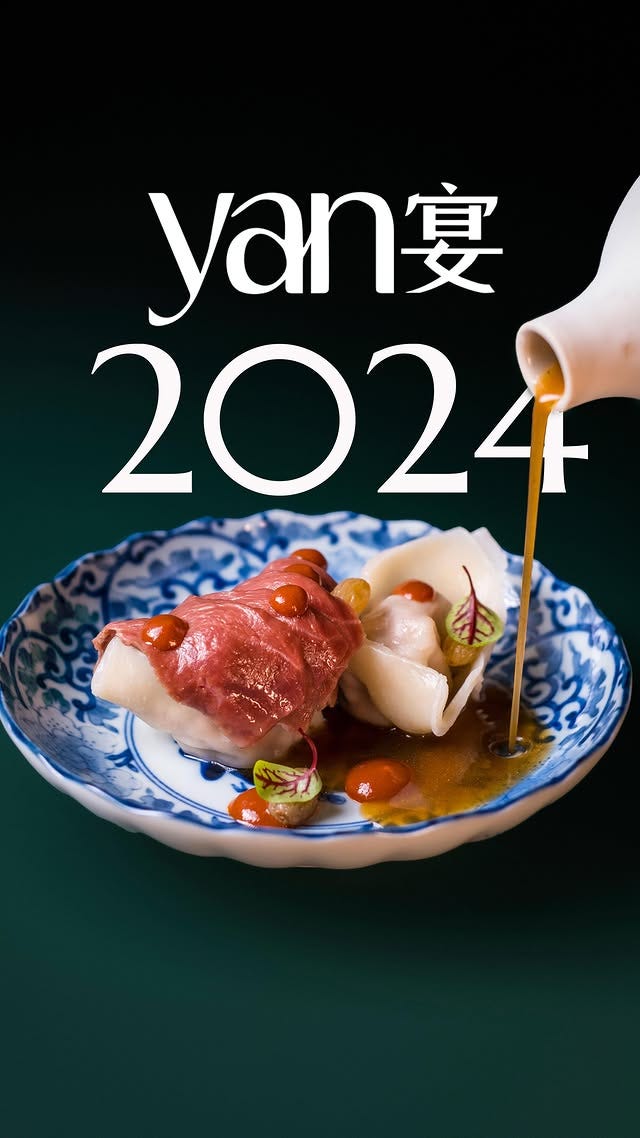

The result: Yan Dining Room, the hidden Chinese restaurant that Chin opened this past fall to great fanfare. At Yan, Chin and her small but mighty team serve up a thoughtful and conceptual eight-course neo-Chinese tasting menu. The flavours are at once nostalgic and new: Chin has a gift for reimagining flavours with a twist that only she could concoct but are yet instantly evocative. An example: When I dined at Yan, chef Chin served a fried sea bream swimming in tart cherry sauce—her play on the classic sweet and sour fish that introduced a new take on the dish while still tasting just as diners remember.

I had the pleasure of chatting with Chin late last year. Here, Chin breaks down her cooking inspirations, the story behind Yan and the future of Chinese food.

Rebecca Gao: You use the term “neo-Chinese” a lot to describe your cooking. What does that mean?

Eva Chin: Neo-Chinese is inspired by the term Neo-Parisian, which is a trend that started 10 years ago when all these master fine dining French chefs and restaurants started producing these amazing young protégés who weren’t actually French. A lot of them were Japanese, Filipino, Canadian, American… just not French. Young chefs who learned under these French chefs for a long time came out and opened their own bistros in Paris.

And these bistros were spectacular. There was no white tablecloth, no tuxedos, no white shirts, no white linen. It was straight up on a wooden table with very, very fun casual service, but the food was spectacular. It had all the techniques that they learned in fine dining, but without the fussiness of fine dining. And a lot of them incorporated their heritage food and how they've adapted to the French taste, so it really embraced the traditions but showed the possibility of what it could be by being diverse. From the second I saw that, I was like, this is what I hope for for Chinese food.

RG: And what was the original spark behind starting Yan?

EC: It started from cooking for friends, and then it became friends of friends and families. And I just realized that in the process of trying to heal my own trauma through cooking the food, other people can also process and heal their trauma by eating. And so I thought, why not? Let's start a pop up, you know? And that just kind of turned into this.

RG: When I came to Yan, you told a story about how you and Colin [the owner of Hong Shing] had this drunk conversation one night which led to Yan being at Hong Shing.

EC: Yeah, we were drunk at a table in like March 2022 or something and we were just spitballing and spewing out little things like, yeah yeah yeah no more than 30 seats and it’ll be like a Chinese omakase and it’ll be one long table. And so we would revisit that conversation every couple of months and I started to feel my creativity come back and I was ready to go back to cooking full time again.

RG: Can you tell me a little bit about that? Why did you lose creativity?

EC: I had major burnout when I left Avling. Like, full-on meltdown burnout. I wanted to not cook. It was incredibly hard to leave Avling and the team. Our hopes were to diversify what was perceived as very caucasian, Canadian brewpub cuisine. And I left because the owner wanted less diversity-driven cuisine. It broke my heart.

So I just couldn’t create. Every time I created food I didn’t know what perspective to go with because I was scared of the same thing happening. I took a year and a half off and during this time, I just really enjoyed not creating food. Yeah, I did pop-ups and collaborations, but it was always driven by a theme, it wasn’t a continuous storytelling tool.

Sometimes, stepping away from it gives you more space to process it. And after a year and a half, it felt natural.

RG: You’ve described Yan as a storytelling tool, what do you think the connection between food and story is?

EC: Food is story. I always thought ingredients were characters and the people producing and writing the story has always been the farmers. I've always thought that chefs are middlemen, and I just want to translate the food from the original story maker through my lens. People often think that Chinese food and the current key chefs are all based in nostalgia, and I don't think that's true, and I don't think that's right to think that way. I think there is something beautiful about being able to be nostalgic with our community and bring up those memories. But it's not just that. There is a future where people are innovating and progressing Chinese food. Part of my storytelling isn't just sharing stories of my childhood, it's always also sharing my hopes and what I want to see, what I'm trying to push, the boundaries I'm trying to cross, and stereotypes I'm trying to break, and the dishes I'm trying to twist. And that's why I always say fusion is confusion.

RG: Is there a dish you’ve created but haven’t served yet?

EC: I love and treasure congee and this dish I have in mind is a sweet congee. I grew up only eating the savouriest of savoury congee. But, during the eighth day of the Lunar New Year, is when you eat 八宝粥, which is a congee with eight kinds of treasures in it. And it’s served cold—actually, maybe it’s just my grandma that serves it to me cold. But my grandma would put crunchy brown sugar on top and I loved it. There are all these textures from chewy raisins to pumpkin seeds. And in my version, all eight treasures will be locally harvested in Canada, it’ll feature eight grains indigenous to Canada and some dried fruits from the summer. It’s everything I believe about farm-to-table and sustainability, but it’s as if my grandmother cooked it. Like, ethnic food is sustainable! It’s been sustainable! The fact that people only think western cuisine can be sustainable is ridiculous to me.

RG: Is there a dish you have the inspiration for but you haven’t figured out yet?

EC: I want to make a menu or a dish based on the four beauties of Chinese history. I'm not sure if you're familiar, but the story goes: there are the four most beautiful women known in history, and they each played a pivotal part in destroying a dynasty. And they also each had a favorite food item. Yang Guifei, for example, her obsession was a type of lychee. So I have been wanting to make a dish that represents the whole story of this tragic lady in a lychee dish, but I’m still working on it.

RG: What are your hopes for the future of Chinese food?

EC: I’ll talk about noodles as an example. The future I hope to see for Chinese cuisine is western chefs making pasta dishes in a wok, because they finally respect that the wok is able to do stuff no other cooking apparatus in the world is able to recreate—you can toss the noodle and they come back to you. My dream is for Chinese cuisine to be seen as mainstream and so valuable that their techniques are incorporated into something as common as a pasta station in an Italian restaurant. It’s not, oh, Chinese people created noodles first or Italian people created noodles first. It's just noodles. Italian dishes can also be made in noodles, and we can also put semolina and egg in our noodles. That’s what I hope for.

Yan Dining Room, 195 Dundas Street West, $88/per person. Reservations (if you can snag them) can be found here.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Three bites I can’t stop thinking about:

🍆: The crispy okra from The Cottage Cheese in Kensington Market. Amazing Indian eats there, especially this appetizer: okra cut into thin matchsticks and deep fried with batter then doused in chilli peppers.

🍣: The Hokkaido scallop hand roll from Hello Nori. Perfectly crisp nori, soft warm rice, and creamy scallop is just a god-tier combo.

🥗: The Caesar salad from The Commoner. This might be basic, but nothing hits like a good, well-made Caesar salad and the one at The Commoner uses deep-fried capers for a bit of extra crunch and funk.